(TZR Reports)

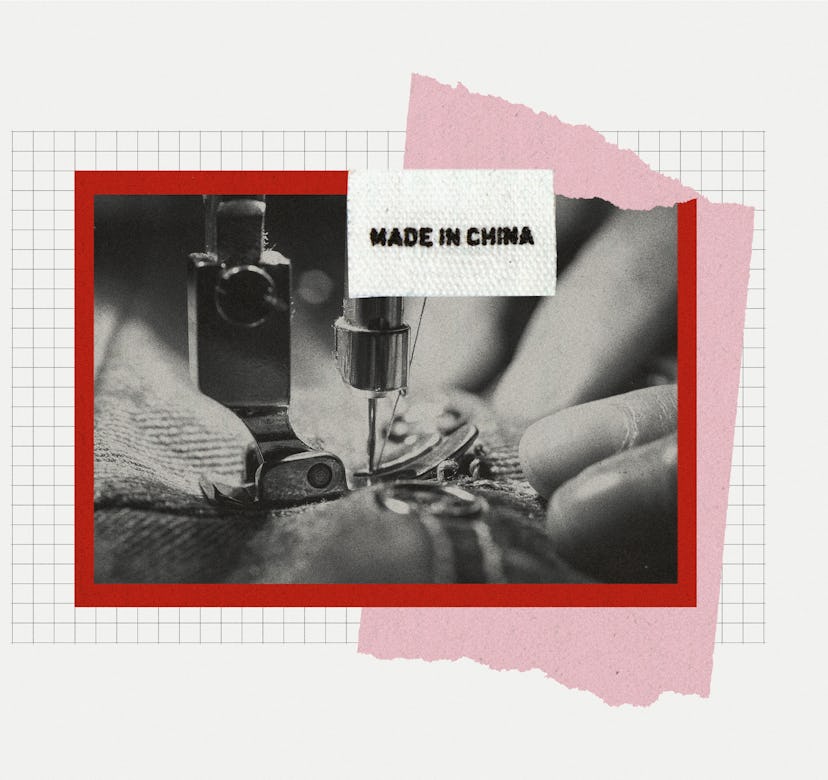

The Complicated History Behind The “Made In China” Stigma

Will it ever go away?

I spent my childhood in the ‘90s watching my mother fastidiously inspect the clothing label of every garment she picked up at our local T.J. Maxx in the suburbs of Michigan. If it read “Made in China,” she shook her head and quickly returned the rejected piece back to its rightful place on the rack. What I was taught — what was drilled into me from an early age — was that anything made in China was bad. Anything made anywhere else was good. And if it was made somewhere in Europe: very good.

Looking back on it now, this was the heyday of the “Made in China” stigma, the perception that Chinese manufactured goods are low quality, cheap, and tainted by something nefarious, be it poor wages, unethical working conditions, or hazardous materials. Thirty years later, the country has undergone tremendous technological advancements, and many European luxury brands have moved their manufacturing to China. But the sense that China-made goods are somehow lesser persists. For instance, when consumers discovered Balenciaga moved its Triple S sneaker manufacturing from Italy to China in 2018, they took to social media to lament unfounded claims about poorer quality or to demand that the Spanish luxury house lower the price of its shoes.

According to Kyunghee Pyun, historian and associate professor of art history at FIT, the Made in China stigma can be traced to the early ‘90s, to when the communist country opened up and entered the global economy in part to assuage pro-democracy sentiments following the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. At the time, Pyun says, the negative perception was warranted. “China entered the cheap, low-end product market; it was not sophisticated production” Pyun explains, especially compared with neighboring countries, like Taiwan, which specialized in high-quality textiles in the ‘70s, or Japan, which made high-end designer goods in the ‘90s. “So, when people say, ‘Made In China,’ they’re reminded of electronics that don’t work or T-shirts that you wash once and the color [fades], or plastic goods that are unsafe, since in the beginning, Chinese companies were [typically] not in compliance with health and safety measures.” Fanning the flames, she adds, were Americans’ post-Cold War suspicion of communism and unfavorable portrayals of Chinese products in media.

But suspicion wasn’t enough to stop American companies from moving production to China. Fashion veteran Su Paek, who founded small-batch, Made in China brand Find Me Now with her daughter Stephanie Callahan in 2020, was working at DKNY in New York City’s Garment District when the industry changed overnight. “All the manufacturing, pattern-making, sewing — everything — happened on Seventh Avenue [in New York City], and then all of a sudden, in a period of five years, it all went to China,” recalls Paek, who began to travel to Asia twice a year to forge relationships with trading companies and factories. “Big companies were already there in the ‘80s, but in the early ‘90s, the medium- to large-size brands, including Donna Karan and DKNY, moved to China — because it was cheaper. And as American consumers, we bought all of that. We supported it.” (DKNY told the Washington Post in 1989 that it mostly worked with Hong Kong factories for cost reasons.)

In 1999, Italian luxury brands rallied to form an association called “Institute for the Protection of the Italian Manufacturers” to protect and safeguard products “Made in Italy” — but within 10 years, many of those same brands are outsourcing to China or other countries. And by then, China’s production capabilities were as good as any country’s. In 2011 Prada was manufacturing 20% of its collections in China. Miuccia Prada told the Wall Street Journal, "Sooner or later, it will happen to everyone because [Chinese manufacturing] is so good.”

Today, luxury brands that manufacture at least some of their goods in China include Coach, Marc Jacobs, Miu Miu, Michael Kors, and Burberry.

Still, you don’t see high end brands touting their handbags’ Chinese manufacturing the way they might if they were made in Italy or France. (One exception is Phillip Lim, who is outspoken about how 3.1 Phillip Lim is proud to manufacture in Shanghai) “Brands that have manufacturing facilities in China should step forward or make the initiative to eliminate the Made in China stigma,” says Pyun. “That’s the ethical thing to do.”

In the world of luxury fashion, the perception of value is as important as the reality of quality. And so when a high-end item is advertised as “designed in Italy” (with no word on where it was made) it’s hard not to conclude that the label believes their consumers think Chinese workers are inferior. Phyllis Chan, former director of knitwear at Rag & Bone who cofounded sustainable knitwear brand YanYan with Hong Kong designer Suzzie Chung, recalls being asked why a sweater made in Scotland was more expensive than one made in Asia. “A lot of the time, I would be super honest and say, ‘Because it’s made by white people, and this is not made by white people’,” she says.

Now, there’s a small, but growing crop of emerging brands that don’t shy away from touting the value of Chinese manufacturing. The playful accessories line Chunks proudly declares that everything is responsibly made in Jinhua, China; direct-to-consumer custom bridal start-up Anomalie celebrates its team in Suzhou, China, lauding their artisanal expertise and dress knowledge. And YanYan’s whimsical Made In China knitwear is not only spun from leftover yarns, but designed with a modern-meets-traditional outlook that’s rooted in Chinese heritage.

“I think it was obvious for us to make YanYan pieces in Dongguan, China, at a factory I’ve worked with for 10 years at my prior job — it’s a super-small company, family-owned, and I trust them,” says Chan. Her one concern about being an openly Made In China company was Western resistance. “But we also really like Chinese crafts, and if you take something like our Bruce Lee-inspired bomber jacket with dragons — wouldn’t it be weird if we made that in Italy?”

Similarly, Paek and her daughter Callahan have remained loyal to their small Jaixing, China-based factory that Paek worked with for 15 years prior to launching their sustainable label Find Me Now. The difference between then and now, Paek says, is that workforce has downsized considerably (from 100 to 20 employees in the office, from 1,000 to 100 in the factory), and workers have all the same benefits as those in the U.S. (eight-hour days, health insurance, vacations, higher minimum wage, 401Ks, pensions).

“When I started [in this industry] 25 years ago, factory workers were working seven days of the week and sleeping in the factories,” Paek remembers. “Now, they’re comfortable. And [with this factory], not only do we know their work and their team, but we also know their family. There’s transparency and trust.”

“I truly believe at the end of the day, the stigma is rooted in racism,” adds Callahan. “With all countries that manufacture goods, there’s a scale. You have low quality and you have high, and it depends on the standards at that specific factory, so to generalize an entire country — the largest country — is not right. All the luxury brands and products we consume on a daily basis come out of China.”

That’s not to say all factories in China boast the same level of transparency or quality as the ones that produce Find Me Now or YanYan products — there are, of course, manufacturers that are exploitative and run on cheap labor. But in Chung’s words, “It’s quite ignorant to assume that what happens at one factory happens to all.”

Another development: It’s no longer cheap to manufacture products in China. In fact, Paek says, it’s actually more expensive to outsource to China than, say, L.A. due to U.S.-China tariffs, a rise in labor costs, and China’s exponentially growing upper middle class.

“The standard of living in China is so much higher now,” Chung says. “Sometimes factories are a secondary business and when that’s the case, you’re going to think, Is this really worth my time to make this stuff? Does this make me happy? [...] They don’t want to do manufacturing or if they do, they want to do higher tech or engineering.”

Pyun predicts the “Made in China” will lose its negative associations in a decade or two, as the production of lower quality products like fast fashion becomes associated with less prosperous countries where labor costs less, such as those in Southeast Asia.

It’s happened before. “In the ‘70s and ‘80s, Japan produced cheap household goods. Same with South Korea, which was mostly exporting wigs and cheap sportswear in the ‘70s. Now, Japan and South Korea create very sophisticated, high-end products,” she explains. “The same thing will happen in China — manufacturing will become more specialized and more profitable, outputting [luxury goods] with the know-how and skills they’ve accumulated over the last 30 years.”

But right now, a new wave of anti-Asian hate in the U.S. threatens to perpetuate the outdated stigma. “COVID just exacerbated xenophobia and bigotry toward Asian Americans and Asian people overall,” says Callahan. Prior to launching Find Me Now, she and her mother had a private label business that designed and produced full collections for fashion retailers that didn’t have in-house design teams, and they were confronted with buyers and clients who were blatantly racist against products made in China. “They said, verbatim, ‘I can’t have things made in China hanging in my shop.’ It was just an overwhelming amount of hate. And it’s only become political now.”

More transparency in the fashion industry has the potential to do more than combat anti-China stigma, says Chung. It can raise awareness of the human aspect of manufacturing, and the human cost of low prices. If it’s an underdeveloped place and you want to help that place prosper, then talk about it,” Chung says. “Whether something is made in China or Vietnam or the U.S. or Italy, it really is, ultimately, a group of people making stuff for you. If you remember that, you’ll be aware that it’s not so faceless. It’s not so automated. It’s people working hard to make your designs come to life.”

This article was originally published on